Bluefin tuna – an iconic example for recovery

Bluefin tuna is known for its size and price. A new management strategy is to ensure the long-term sustainable management of the stocks in the Atlantic.

On the 21st of September 2022, plans were announced by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation and WWF to convene a Business Coalition for a Global Plastics Treaty. Following last year’s efforts to induce the United Nations to agree on the development of an international framework regulating the plastics cycle, which resulted in a UNEA resolution in March 2022 titled “End Plastic Pollution: Towards an international legally binding instrument”, this year’s efforts are aimed at bringing a clear and unified voice of businesses, financial institutions, and NGOs to the treaty negotiations to support the development of an effective and ambitious treaty.

The coalition supports the following key elements in particular:

In order to better understand why such a treaty is needed in the first place, this article will now take a closer look at the world’s current and future plastic production, how plastics are being managed, how they affect our health and, of course, also our oceans and seafood. Additional details on the coalition and its objectives are available here.

As of today, the world produces roughly 220 million tons of plastic each year, of which only 15% is being properly recycled. A further 15% is effectively dealt with by incineration, but the rest is either burned in the open or stored in landfills, from where it can gradually leak into the environment. As a result, every year, roughly 11 million tons of plastic end up in the ocean – 10 million tons of macroplastic and 1 million tons of microplastic. The Pew Charitable Trusts and SYSTEMIQ estimate that the share of macroplastic purposefully discarded into rivers and oceans may even be as high as 60%. This alone should be enough to understand that a minimum global standard is desperately needed.

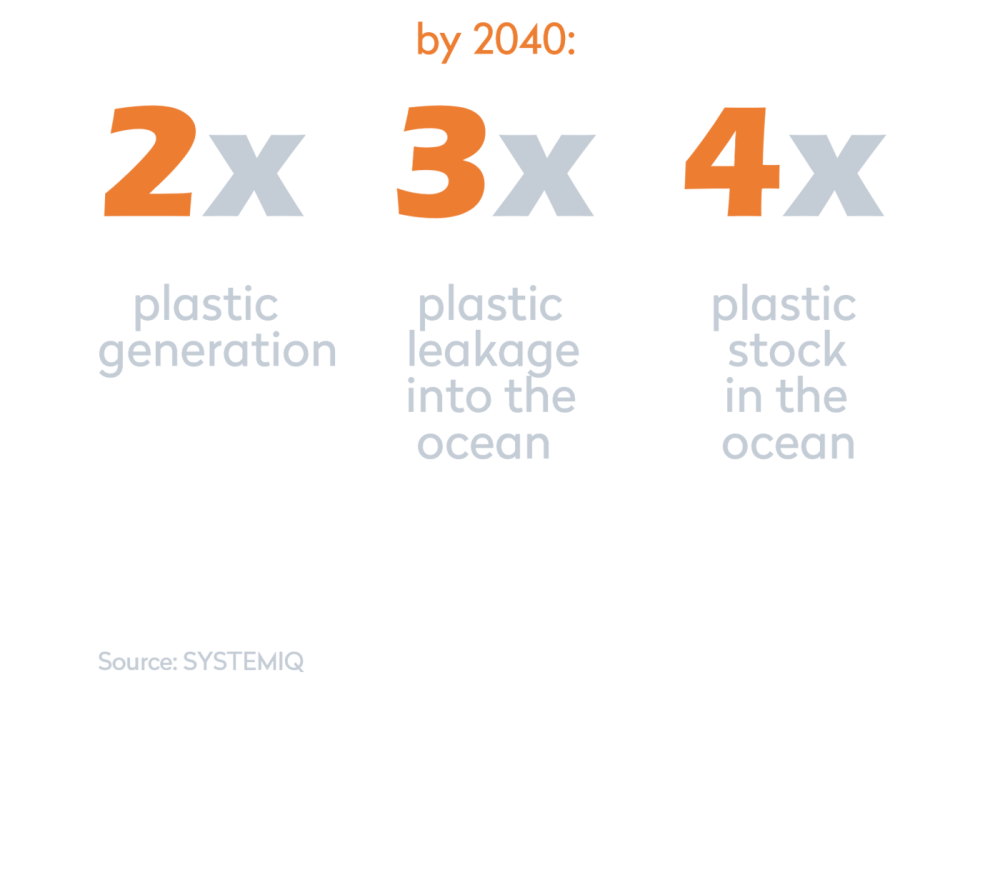

Unfortunately, in a business-as-usual scenario the situation is only going to get worse. Plastic production is widely expected to double in the coming 20 to 30 years, representing virtually the only real source of growth for oil producers going forward. Since much of the growth in plastic consumption will take place in countries with less advanced waste management systems due to population growth and rising per capita plastic consumption, plastic leakage into the ocean is even expected to triple and total plastic accumulated in the ocean will roughly quadruple. In terms of climate change, this also implies that about 20% of the 1.5° carbon budget will be used up by plastics alone.

While larger pieces of plastic can be a danger mainly to animals, microplastics are probably of much greater concern to humans. Microplastics are commonly defined as plastic particles 0.1 to 5,000 micrometers (i.e. 5mm) in size. They can be grouped into two categories, primary and secondary microplastics. While primary microplastic is released directly as microplastic into the environment, secondary microplastic gradually originates from the degradation of larger plastic waste.

Synthetic textiles (35%), tire wear (30%), which happens to only worsen with the increasing adoption of electric vehicles, and city dust (25%) are by far the main sources of primary microplastics.

Studies analysing microplastics (and nanoplastics for that matter) are still somewhat rare, so it is difficult to make reliable assertions. However, there are studies claiming to have found plastic particles in human blood and lungs. It is estimated that through routine food and beverage consumption, humans ingest up to 5 grams of microplastics per week - roughly equivalent to eating one credit card.

Can that be healthy? Probably not, no. Is it unhealthy? At least not in an obvious way at the current concentrations. In general, there are three components of plastic that might harm us. The plastic itself, additives to the plastic, such as antioxidants, UV-stabilizers, plasticizers or flame retardants, or pathogens surrounding the plastic. While there are studies that show negative effects on human cells, such as inflammatory reactions, those studies were usually conducted with unnaturally high concentrations of plastic, far beyond what we might involuntarily consume. The old saying, the dose makes the poison, therefore seems to hold at least partially true after all, although toxicity certainly also plays a role.

One food often assumed to contain particularly concerning concentrations of plastic is seafood. That is why in 2016, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) set out to calculate the amount of plastic and additives consumed through seafood in a worst-case scenario. They analysed mussels, which we eat - unlike most fish - together with their gastrointestinal tract and which should therefore contain more plastic particles than most other seafood. The results show that even mussels are perfectly safe to eat. Using the highest amount of microplastics found in mussels, a portion of 225 g of mussels could contain only 7 micrograms of plastics and less than 0.1% of the additives a person is normally exposed to from other sources through a typical diet (with bottled water being one of the main culprits). Concerns about seafood, therefore, seem greatly overstated. Airborne plastics, which tend to be smaller and are thus able to penetrate barriers more easily, rather merit our attention.

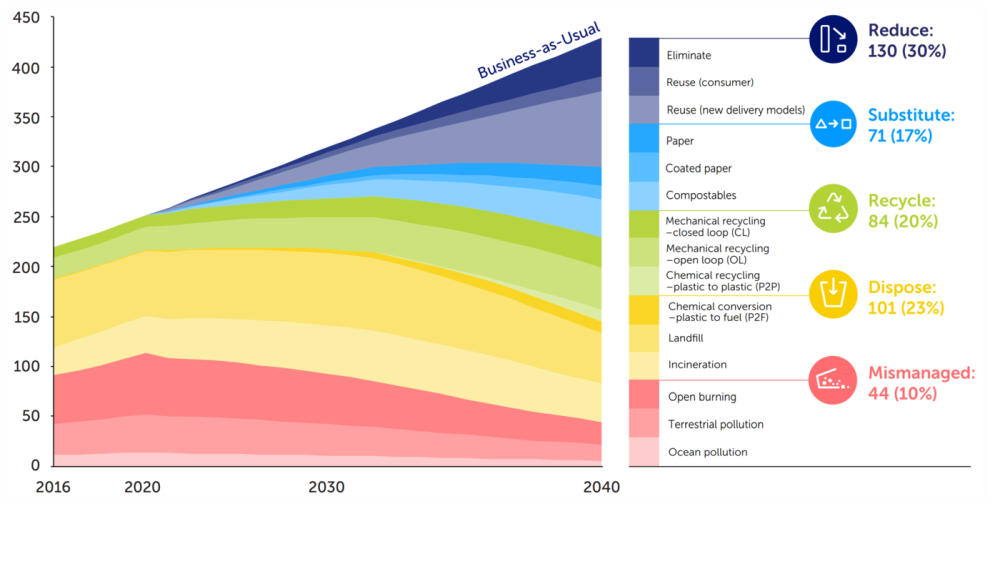

Going forward, it is important that governments quickly agree on and implement an ambitious plastics treaty in order to ensure that the situation does not deteriorate further. As the diagram below shows, alternatives to the business-as-usual scenario that keep plastic pollution at least around current levels are conceivable. With our support of the Business Coalition for a Global Plastics Treaty we hopefully get one step closer to achieving this.

Comments