1. Chile Report: Salmon Farming

At the beginning of 2019, we took the opportunity to visit salmon farming operations in the Chilean summer.

The world keeps turning and facts keep changing. Just as today cars use far less fuel per kilometre than before, the aquaculture industry is making enormous progress in the environmental sector. But once people, and obviously scientists too, have voiced an opinion, they find it difficult to acknowledge when things have changed for the better. A few potshots against aquaculture in a radio interview have turned out to be a violation of the scientific maxim always to use the latest data.

While sitting in my car during the summer of 2021, I heard this programme (in German) about the river migration of wild salmon, which came to an end in the Rhine decades ago, probably as the result of human activity. But as is so often the case in such considerations, the programme also contained a few potshots against successful salmon farming without any real context. Although the numerous advantages of aquaculture far outweigh the few disadvantages, the industry obviously makes certain people feel uncomfortable. Perhaps the industry is still too young. With poultry, pigs and cattle, most people never believed in the idyll of wild animals. At Bonafide we are familiar with the scientific facts of aquaculture, and for this reason I like to turn up radio programmes of this type to hear whether the statements expressed correspond to my knowledge base.

The expert quoted is a biologist and scientist, so neutral listeners should be able to rely on her to explain the facts “in good faith”. The editorial team at the Swiss national radio station SRF should also be able to be counted on for their status as experts. To my great astonishment, I heard three statements that are significantly different to what I remember. First, the biologist accuses the salmon industry of farming one kilogramme of salmon at the expense of 2-3 kilogrammes of wild fish. Second, she claimed that the industry is contributing to the eradication of wild fish. And thirdly, she stated that farmed salmon eat wild fish at the expense of humans. As a financial analyst, I felt inferior to a trained biologist and scientist in this area, so I quickly began to question my sources. One thing I knew I had to find out immediately was this woman’s sources, as my renewed research confirmed the facts as I remembered them, which in no way matched the negative statements made on the radio.

In an email to the SRF editorial team, I began to compile my sources with a friendly request for information on the exact scientific sources the expert was relying on. After about two months without receiving a response, I persisted and politely contacted the SRF again via email. Based on my understanding of the facts, I did not want to leave these false statements on the radio unchallenged. I had all but given up when, to my great astonishment, after another month I received an answer. My first email had not reached the right person, and the response to my second email was delayed by a few days due to staff holidays. Much more important than the apology, however, was the provision of the scientist's source of information. Quote:

«The interviewee XY is a biologist and scientist. She researched the data for her book “The Salmon. A Fish Returns”, published in 2011, and had it checked by the WWF. She is essentially referring to these data in the interview. In response to your enquiry, I contacted her again and she continues to stand by these statements.”

Voilà! One of the most fundamental commandments in science is to make sure you are up to date with the latest data. However, this real-life example shows that not everyone lives and works according to this “maxim”. The biologist's sources are not fundamentally wrong, they are simply out of date! Imagine if nutrition experts from UN organisations were to advise the governments of Africa today on the basis of the population in 2010. The 300 million people who now live on the continent in addition to the 2010 population of 1 billion, would be excluded from strategically important decisions. Famine would be inevitable. The metaphor is far-fetched, but it shows how much things can change in a short period of time. For us, the question arises as to whether it really makes sense to present the public with 10-year-old data that is long out of date.

We would like to update the three outdated facts in a transparent matter. Regarding the issue of feeding farmed salmon on wild fish in the form of fish meal and fish oil mostly from anchovy species, since 2013 the value in Norway has been 0.7 kg instead of the 2-3 kg that was common before 2010. The study by Nofima, published in 2015, is publicly available. The allegation that farmed salmon are contributing to the eradication of wild fish stocks can be refuted by the fact that even NGOs such as the Marine Conservation Society today rate fisheries of this type and species positively. This rating refers to the largest fishery for fish meal and fish oil, which is located in Peru and Chile. Further proof of the stable, monitored biomass of anchovies in Peru is provided by Austevoll Seafood, which is in our portfolio and is involved in the fishery. Every quarter, in the reports on page 5 of the presentation, the multi-year development of the biomass is listed. This has been showing steady development for almost 20 years.

For the third allegation that farmed salmon eat wild fish at the expense of humans, the International Fishmeal and Fish Oil Organisation (IFFO) has published a case study on its website which addresses precisely this problem. This type of anchovy in Peru and Chile grows to a maximum length of 10 centimetres. It is simply not possible to process these odorous fish into edible fillets. And for the entire fish, there is simply not enough demand to sell the annual, sustainable catch. This fish, with production costs of less than 40 cents per kilogramme, would be so cheap that the industry would be very interested in a market for human consumption. All in all, the salmon industry and its suppliers, such as the anchovy fisheries, have made significant advances in just a few years. Further progress can be expected thanks to numerous ongoing efforts to improve sustainability.

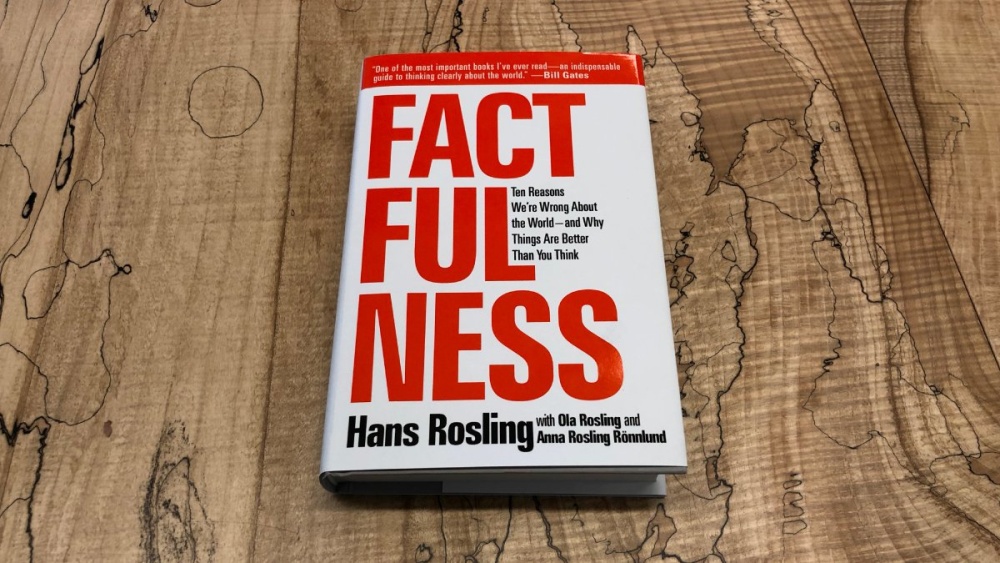

On the subject of outdated facts, we have a book recommendation for you. The statistician and scientist Hans Rosling, who has unfortunately since passed away, published the book “Factfulness: Ten Reasons We're Wrong About the World--and Why Things Are Better Than You Think” in 2018 with his daughter-in-law Anna Rosling Rönnlund and his son Ola Rosling. Influenced by lurid media headlines, everything on earth is getting worse and worse. The rich are getting richer, the poor are getting poorer. War, violent crimes and natural disasters are on the increase. With the help of impressive statistics and facts, Rosling refutes numerous biased worldviews. In fact, the world is improving and becoming more bearable for the general population in many respects. The book also shows the importance of using up-to-date information. What we learned about Asia and Africa in school 20 years ago from a Western viewpoint is simply not applicable today. In an entertaining way, the book helps us to get away from sensational hypotheticals and instead to rely on facts. If you do not have the time to read the book, you can also watch a recorded TED talk with Hans Rosling for free.

How not to be ignorant about the world | Hans and Ola Rosling

Comments