Who doesn't know them: those people who prefer wild fish from Alaska to inferior farmed salmon because of its natural origins. It also simply tastes better. The reality is quite different. As early as 1970, hatcheries were established in North America, initially to stabilize catch yields and later even to increase them. Today, around one in three “wild salmon” caught in Alaska originally comes from a man-made hatchery.

Whether Lake Zurich or Alaska

It doesn't even have to be Alaska. Every year, between 50 and 100 million local small fish are released into Lake Zurich. This results in a modest wild catch of 200 tons. That is around one-fifth of a single (!) net of farmed salmon in Norway and is enough for around 600,000 meals. The breeding station in Stäfa on Lake Zurich has been in existence since 1942. Even back then, it was clear that ecosystems were changing and that human intervention was necessary to preserve the species. In order to avoid interfering with genetics, spawning fish are caught in the lake. The small fish hatch from their eggs in the breeding stations and are fed before being released back into their native waters once they reach a certain size. The same thing happens, incidentally, with the management of countless rivers and streams, where fishing clubs have been releasing fish of various species for decades because natural reproduction has stagnated.

Wild catch volume fluctuates greatly

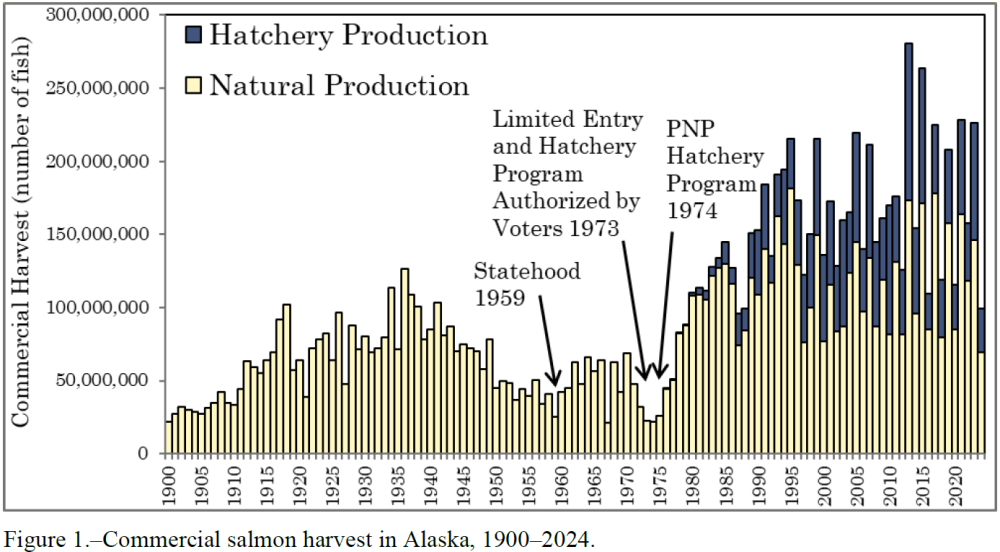

In Alaska, the hatchery program was launched in the 1970s after a further decline in the harvest to around 25 million salmon threatened the most important industry and thus prosperity. Today, there are 26 such hatcheries in Alaska. Catch data dating back to 1900 show that there has always been great volatility in the return of salmon to their spawning habitat and thus in the harvest. Food security for the growing population of the USA with wild salmon was questioned. The breeding program seemed to have contributed to a rapid recovery of stocks. Not only were more hatchery salmon caught, but the harvest of salmon that reproduced entirely in the wild also increased. In the peak year of 2013, 97 million of the nearly 280 million salmon caught originated from hatcheries – that is 35%. In general, the annual catch after 1980 doubled compared to the previous 80 years.

The wilderness is a brutal place

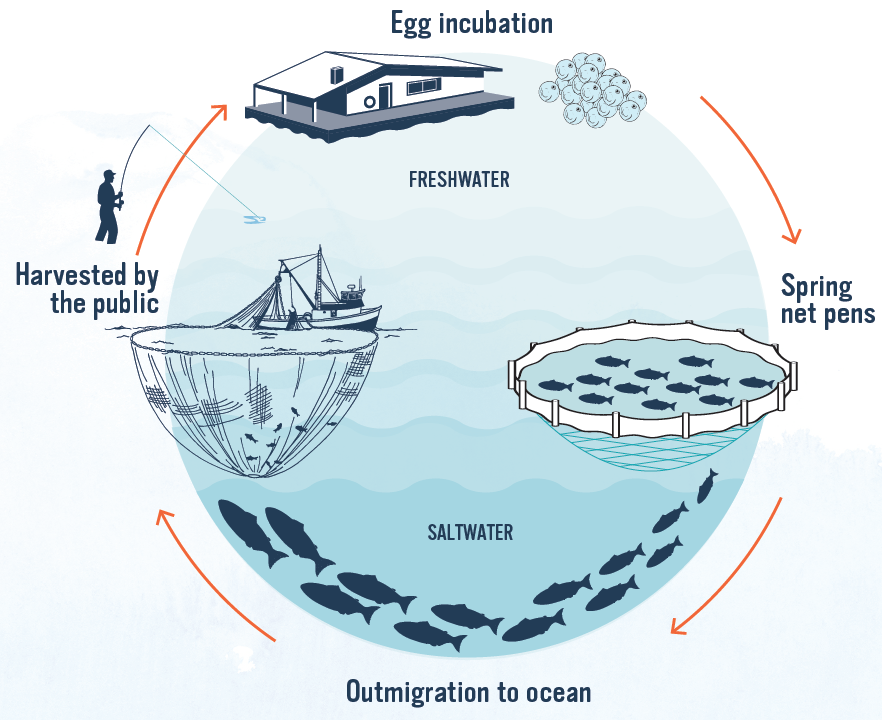

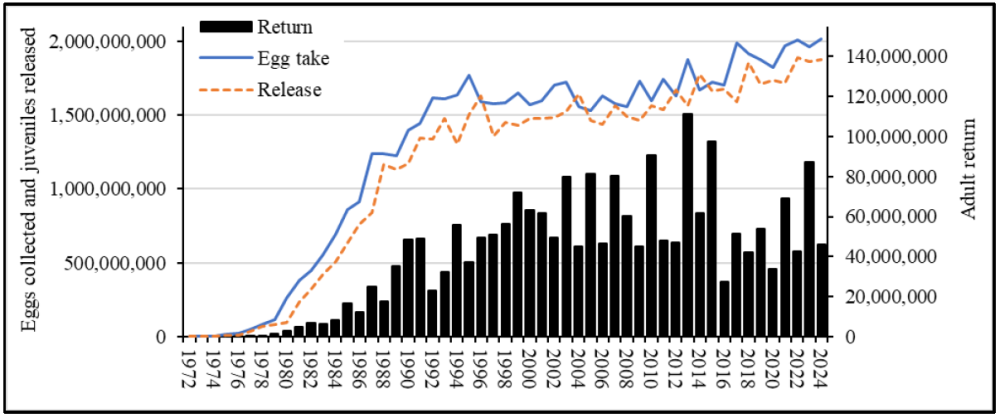

Unlike aquaculture, which covers the entire life cycle, hatchery salmon are released into the wild during the expensive feeding phase in the hope that they will return well-fed in a few years. Currently, 1,800 million animals in robust condition are released into the sea in Alaska every year. The return rate has consistently been below 5%. The remaining >95% do not survive the marine cycle; it can be assumed that they end up as food for larger predatory fish. Overall, however, the venture still seems to be worthwhile for the Alaskan fishing industry. Morally, one may ask whether a survival rate of around 85% in breeding or a 5% chance in the wild is better for the fish. Anyone who thinks that the Alaska model can simply be copied by other coastal nations such as Norway is comparing apples with oranges. Factors such as climate change and intact river systems without human intervention still need to be taken into account. 150 years ago, salmon also swam in large numbers in the Rhine as far as Switzerland, but they have been considered extinct since 1950.

Farmed salmon versus wild salmon

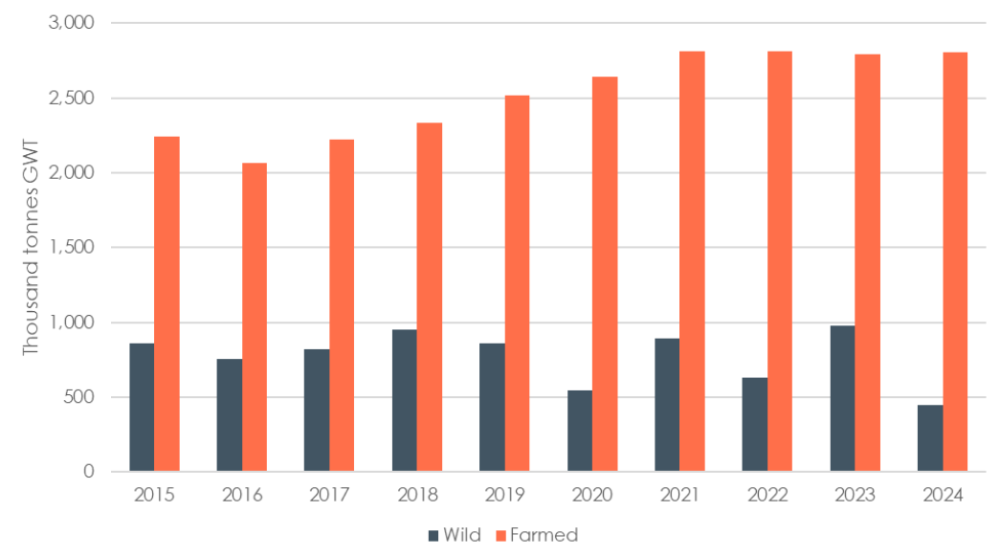

Pitting the two types of fish against each other does not yield a clear result. The nutritional values of protein and omega-3 fatty acids are practically identical and depend on effective food intake. Wild salmon could absorb toxic substances or microplastics in the sea in an uncontrolled manner, while farmed salmon could be fed a poor-quality diet. However, farmed salmon has a clear advantage in terms of seasonality. Fresh wild salmon from Alaska is available from May to October, but is usually frozen due to the transport route. For farmed salmon, which is harvested daily throughout the year, a value chain has been established that can ship fresh fish to virtually every country in the world within 2-3 days.

Conclusion

Alaska and Switzerland can claim a piece of aquaculture history. However, the myth of wild salmon is rapidly losing its significance as more and more fish spend the first stage of their lives in hatcheries. It is understandable that people want to live in harmony with nature, but a planet with soon to be 10 billion hungry people awaits us. Food security is becoming a central issue, and luck or hope for good wild catches from Mother Nature has no place here. The future belongs to holistic aquaculture – perhaps even in Alaska at some point.

Comments